Bob Weir died on a Saturday.

That detail matters—not because coincidence proves anything, but because Bob Weir spent his life teaching us how symbols work. Saturday was never just a day of the week in the world of the Grateful Dead. Saturday was the release valve. The night you played like there might not be a tomorrow. The night you emptied the tank because the crowd deserved it and the music demanded it.

“One More Saturday Night” is a beloved anthem that’s about more than just partying. It was about staying upright through the week and arriving battered but willing. Bob Weir died on a Saturday, and even in his departure, he somehow still commanded the stage.

I never met him. Like millions of others, I knew him through records, bootlegs, stories, and one very good show a few years ago with Dead & Company. But the shock of the news felt personal anyway. That’s the strange power of artists who build not just songs, but communities.

You don’t have to meet them to lose them.

It feels appropriate, somehow, that I didn’t hear the news in a grand or ceremonial way, or while mindlessly scrolling something and getting that breaking news alert.

My cousin and godmother Kristine texted me—a Facebook post, already shared and reshared, already absorbing comments and memories. She’s the one who got me into the Grateful Dead when I was in middle school.

I wore a tattered Scarlet Begonias tie-dye throughout high school that she scored on the lot at the final show at Soldier Field in 1995. I was busy when the texts came in. I was running around after my own kids, moving through the small logistics of an ordinary day. I was also planning a show of my own for the next night—thinking about setlists, transitions, how to hold a room, how to give something of myself to the people who would show up.

That felt right, too.

This music has always traveled sideways—through parking lots, phone calls, tapes handed from one person to another. Of course the news came that way. Of course it arrived while life was in motion. That’s how this whole thing has always worked: the song keeps playing while you’re busy being who you are.

What I’ve been thinking about all day isn’t just Bob Weir’s death. It’s the weight of what he carried while he was alive.

For sixty years, Bob Weir played this music. For half of that time, he played it in the absence of Jerry Garcia, the band’s gravitational center and mythic torchbearer. Before Garcia’s death, there was Pigpen. Then after it was Keith Godchaux. Then Brent Mydland. Then one after another, the circle thinned. And still, Bob stayed.

There is a particular kind of courage required to keep showing up when the ghosts keep multiplying.

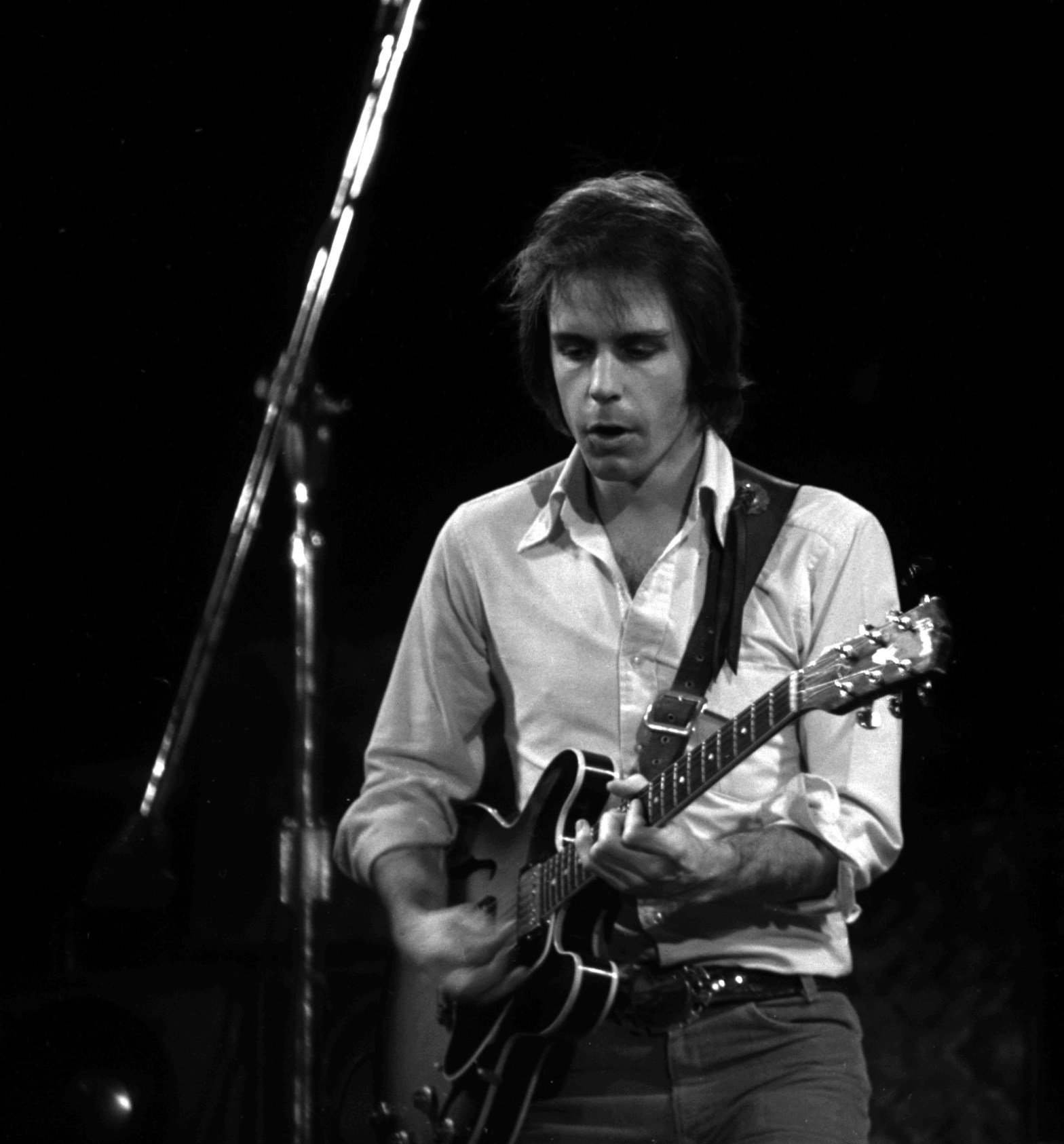

Late in life, videos would surface of this seventy-something man schooling musicians half his age—not just musically, but physically. He still commanded the stage. Anyone who has ever tried to stand on a stage—small, medium, large—knows that command isn’t about ego. It’s about presence. Bob Weir had it until the end.

If Jerry Garcia was the river, Bob Weir was the shoreline. Angular. Rhythmic. Percussive. His jingle-jangly guitar style didn’t float—it pushed. He created tension. He created space. He made the music walk upright instead of drifting away.

Bob Weir’s songwriting (alongside John Perry Barlow) did the same thing.

His songs gave us lyrical hooks that still rattle around the collective consciousness—short lines, almost aphorisms, that feel older than the records they’re on:

“Ah mother American night,” from Black-Throated Wind, a song about exhaustion, motion, and the cost of always being on the road.

“Let your life proceed by its own design,” from Cassidy, part benediction, part instruction manual, offered without judgment.

“Leaving Texas, fourth day of July / Sun so hot, clouds so low / The eagles filled the sky,” from Jack Straw, a road movie compressed into a breath, already tinged with consequence.

These aren’t dated lines. They’re durable ones. They function the way folk wisdom does—simple on the surface, endlessly reusable.

And then there are the lines that don’t announce themselves as wisdom at all—the ones that just worm their way in and refuse to leave:

“Forced me to see you’ve done better by me / Better by me than I’ve done by you,” also from Black-Throated Wind, one of the most quietly devastating admissions in the Dead’s catalog.

“Moses come ridin’ up on a quasar / His spurs were jingling, the door was ajar,” from The Greatest Story Ever Told, where scripture, psychedelia, and frontier myth collapse into a single surreal image.

These aren’t slogans. They don’t resolve neatly. They stick because they feel overheard rather than declared—fragments of thought that mirror the way memory actually works. Bob Weir’s lyrics arrive sideways, carrying moral weight without ever quite telling you what to do with it.

After a while, the lines stop belonging to individual songs and start forming a private interior soundtrack: “The heat came round and busted me for smiling on a cloudy day,” “No one’s noticed but the band’s all packed and gone / Was it ever here at all?“, “The bus came by and I got on, that’s when it all began”, “I need a miracle every day.” They surface unannounced—in the car, on a long walk, halfway through a hard day—less like lyrics than like remembered instructions.

That’s the quiet miracle of Bob Weir’s writing: the songs don’t just play; they reappear, years later, exactly when you need them, still angular, still restless, still asking you to keep moving.

The Grateful Dead didn’t just cover songs; they activated them. They treated the American songbook as a living platform—something you step onto, not something you preserve behind glass. Long before the internet, they built distributed communities of people who traded tapes, traveled together, and learned how to listen collectively. By the time digital networks arrived, Deadheads already knew how to be there for one another.

Bob Weir stood at the center of that for decades—not as the messiah, not as the myth, but as the steward. That role is harder than it looks. It means playing songs you’ve played thousands of times as if they still matter. It means honoring the past without embalming it. It means absorbing criticism about money, touring, branding, reunions, and logistics—what happens when a countercultural aircraft carrier keeps sailing long after the world expects it to sink.

People complained. People always complain. But the truth is simpler than that: Bob Weir did the work.

His longevity wasn’t just physical stamina. It was emotional endurance. He carried grief without turning it into spectacle. He carried joy without pretending loss hadn’t shaped it. He carried the music forward so others could encounter it fresh—sometimes for the first time.

When I think about Bob Weir’s death, I can’t help thinking about my own life with music—playing it, collecting it, teaching it, using it as a way to gather people into rooms, literal and metaphorical. Music is a thread. It binds decades together. It makes memory communal. It reminds us who we were and gives us permission to keep becoming something else.

Bob Weir understood that. He lived it. And on a Saturday—of all days—he left the stage having done exactly what he always did: show up, play the song, and trust that someone else would carry it next.

One more Saturday night, indeed.